Advent Sunday 1654 was not a happy day for the seventeenth century English diarist John Evelyn, on account of, “There being no office at the church but extempore prayers after ye Presbyterian way, for now all forms are prohibited and most of the preachers were usurpers.” Things were to get worse. On Christmas Day 1657, Evelyn went to church with his wife. “The chapell was surrounded with souldiers, and all the communicants and assembly surpriz’d and kept prisoners by them.” Eventually they were allowed to take Communion but, “As we went up to receive the Sacrament the miscreants held their muskets against us as if they would have shot us at the altar.” Christmas had been effectively banned by the Puritan Government of Oliver Cromwell. The ban lasted from 1647 till 1660. The Puritans thought Christmas to be a superstitious festival for which there was no Biblical warrant. They were also suspicious of the use of the old Book of Common Prayer which was “nothing but the masse in English,” and the potential for the festival to be a rallying point for Royalists. But underlying their ban was the Puritans’ desire to change society, and to rid it of secular enjoyment under the cloak of religious observance. That they were unsuccessful is suggested by the sermon that Evelyn records two years after the lifting of the ban in 1662. He noted that the curate had preached on “how to behave ourselves in festival rejoicing.”

This year there have been references back to those days of a banned Christmas, as we contemplate a festival constrained by regulations, which differ from country to country, but which rarely allow for “Christmas as we know it.” Hopefully that will be a one-off experience and, in any case, will not involve soldiers with muskets. But there is one attitude of those seventeenth century days which still persists, and that is the overt puritanism which sees Christmas, as it is celebrated in society at large, as something to be dismissed and judged. Christmas is only real in Church. We are the franchise holders!

I heard a rather garbled version of that view expressed on a BBC radio news programme just last night, by an English bishop. What I learned from the experience of listening to it was that it is impossible to throw things at the radio if you are simultaneously holding your head in your hands. In order to be an effective representative of Christianity in the public square of the BBC, you need to be fluent in two ‘languages.’ One is the ‘language’ of the Bible. You need to understand its idioms, to recognise its nuances, to be familiar with the tools it uses to persuade us of its truths. Unfortunately so many who claim to speak for Christianity have only a passing acquaintance with this ‘language.’ They are not fluent. They have ‘tourist Bible’ of the kind that enables a monoglot English speaker to order paella and chips in Spanish. The other ‘language’ is the language of ordinary everyday life and culture, and again so many of our spokespeople seem completely unaware of it, as if they live on another planet called ‘Church.’ There is a deep irony in speaking about Christmas from this level of ignorance.

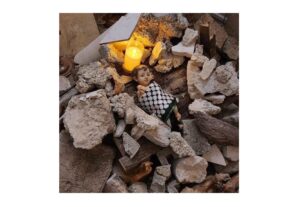

The texts that accompany our Advent and Christmas journey, among the most theologically dense in the Bible; usually, speak about incarnation as a way of discerning the divine in the midst of the ordinary. That, I think is one of the things that gives this season its popular appeal. On the one hand it gives us access to a picture of transcendence and mystery, yet it is a picture conveyed in a story that can be owned and rehearsed by children. The question that the BBC bishop responded to was this: in our constrained circumstances, how can we rescue or recover Christmas? The answer should have shown some understanding of what the secular celebrations try to embody, and what ordinary people understand by Christmas. For most people the concept of Christmas means, at a rough guess some or all of the following. It is a time to value friends, family, community and society. It is a time to give and receive gifts. It is a time to celebrate, be joyful and resist heroically the darkness and cold that accompanies the festival in North Western Europe. It is a time to consider the plight of the cold, hungry naked and lonely. It is a time of hopefulness, a time of festivity; a time to recall the importance of tradition. That is the Christmas that we, the people, have invented since the Puritan lockdown, a subversive festival when we assert ourselves by doing what we know we may well regret when we measure our waistlines in the new year. But it is a Christmas rich in theological possibility.

And in church we need some humility in relation to that. We need to, in a sense, respect that; because that is what those who come to church bring with them. And what they do there, if it works, is to make connections between those fundamentally human longings and expectations, and the much bigger picture of a faith that shows us how to be truly human, and provides us with a framework on which to hang a world view. That is what theology is. That is how the conversation can be conducted. Christmas is a people’s festival, and it will persist, as history has proved. It is not the possession of some Church establishment, though the Church certainly has a vital role to play; and has contributed much to our understanding of it. Christmas makes theologians of us all.