Reflection—Canon Theologian John Holdsworth

A few days ago, I was taking part in a Bible study in Egypt. The task before the gathered group was to try to make some theological sense of what is happening on our doorstep in Gaza and Israel. It soon became clear that for the group the main theological question that had to be faced first was this: is the Israel we read about in the Bible coterminous with the modern State of Israel? The answer to that question determines how the rest of the discussion will proceed. If the answer is yes, then we shall sympathise with and understand those settlers establishing armed compounds within Palestinian areas. We shall be in accord with those right-wing evangelical Christians in the United States that are part of the Israel lobby there, and we shall see the point of Jewish expansion in Jerusalem.

If the answer is no, then we shall see this conflict, and judge this conflict as we would judge any other bloody conflict anywhere in the world, Ukraine for example. We shall judge motives and analyse the dispute according to accepted secular standards. The role of religion in the conflict will be quite different, and will concentrate on issues of peace, justice, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Whatever our choice, this is not an invitation to pick a side in the conflict. It is convenient for us to see good guys and bad guys, but it is a lazy and dangerous option to do so. Since the early 1980s, the Churches’ analysis, in Britain at least, based on the findings of two separate delegations from the then British Council of Churches (one of which I was a member of) was that the events in Israel/Palestine have to be seen as the result of two wronged peoples, unable to escape from the consequences of the abuse they have endured. Each now apparently delights in causing suffering for the other, and in such a situation it is difficult to be optimistic of a good outcome without some third, neutral partner.

But, back to the main question. Is the Israel we read about in the Bible coterminous with the modern State of Israel? Actually, we see debate in the Bible itself and certainly in modern scholarship about it and about who constituted “Israel”. Since the 1950s, Old Testament scholars have believed that the most ancient “people of Israel” did not just consist of descendants of Egyptian slaves. Rather, in this late Bronze Age period there was a great deal of migration around the eastern Mediterranean area, and the thinking is that the Exodus slaves were joined by many of these migrants to form “Israel”. In other words, the story of Israel would have been rather like the story of modern America. People fleeing religious persecution were joined over centuries by others from various backgrounds of oppression who found asylum there, and this whole melting pot of people became “Americans”.

What is important, these scholars would say, is not the DNA or ethnic background of the “people of Israel” but rather their willingness to sign up to the Covenant that God had made, as summarized to some extent in what we have come to call the ten commandments. George Mendenhall, a respected Old Testament scholar, makes the case for calling them “the ten commitments” on that basis. Israel is not a nationalist people first but rather a covenant people. Of course, this idea sometimes gets lost along the way and in the prophets we see constant reminders of that covenant basis.

In the New Testament too, and particularly in Matthew’s Gospel, we see the point reiterated. John the Baptist’s preaching is unmistakable.

“Prove your repentance by the fruit you bear and do not imagine you can say ‘we have Abraham for our father. I tell you that God can make children for Abraham out of these stones’” (Matthew 3:8,9).

The Gospels have many references critical of any idea of Jewish privilege or entitlement. People are members of “Israel” by virtue of the evidence they can show of maintaining the Covenant demands of justice, mercy, truth, love. The most modern scholarship on Paul’s letters also believes that much of what he says about salvation through grace by faith refers, in the first instance, to membership of “Israel” rather than something more general about salvation. In Galatians, having written about appropriate Christian behaviour in God’s new creation, of which he believes Jesus is the second Adam, Paul writes:

“Circumcision is nothing. Uncircumcision is nothing. The only thing that counts is new creation. All who take this principle for their guide, peace and mercy be upon them, the Israel of God” (Galatians 6:15).

It is difficult to see any of the Covenant requirements by either side in the current conflict. Rather we see the presence of God in the sacrificial service of those caring for the sick and injured, those working for reconciliation, those who care about the human needs of others because they see them as people like ourselves and not as some other lesser species; those who do not exult in the massacre of thousands but in the saving of a single child. There is no rejoicing in heaven over any so-called military victory. There is rejoicing in heaven rather over one sinner who repents.

Still, some of the members of the Egyptian Bible study were uneasy. Surely the Book of Revelation has things to say about the role of Jerusalem in the end times does it not, and these feel like the end times. Well, when the book of Revelation was written it felt like the end times then, and it has felt like the end times many times since, including during the Crusades, to take just one example. The language and idiom of Revelation is not to be understood literally. The original hearers even would not have understood it in that way, in all probability. But the message—that God has a plan for history, and will see it through—is the one that perhaps we need to see more clearly. Revelation is not an ancient kind of Old Moore’s Almanac, predicting the future as astrologers do.

What is happening in Israel and Gaza is tragic. We, the covenant people of God, the Israel of God, have a responsibility to be part of the loving, compassionate praying and caring response to the problem, and not part of any triumphalist, entitled cause of it. At least our own Egyptian “peace summit” by the side of the Red Sea, was agreed on that.

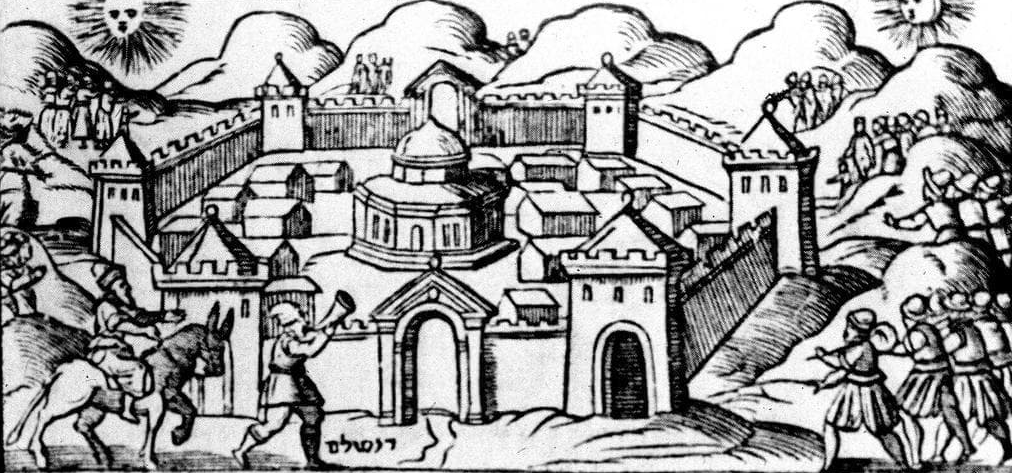

Image: Jerusalem, Venice Haggadah, 1609

Credit: www.sefaria.org