Many people have been fascinated by our first opportunity to experience the Accession Council, as part of the process of transition following the death of HM Queen Elizabeth II. As a BBC commentator said without a trace of irony, ‘This is a ceremony a thousand years old, but this is the first time it has been shown on television.’ One of the striking things about it was the extent to which God was seen to be a player. God was mentioned several times as an orchestrator of events and, also, as the supporter and energizer of the monarchs past and (now) current. The announcements have all concluded with the words “God save the King,” prior to a singing of a national anthem which is, in fact, a hymn. It might be concluded that this simply reflects the mediaeval idea that kings rule by divine right (as opposed to bishops who only have divine permission) but in fact the relationship between our religious tradition and kingship is far deeper and more contemporary than that.

Kingship is one of the major themes of the New Testament. The opening of Mark’s Gospel is not unlike the Accession Proclamation: God’s rule as king has now begun! (Mark 1:15). The kingly rule of God is a theme throughout the Gospels, as the writers describe Jesus’s attempts to adequately portray what this rule, this reign, will be like; how it will differ from current society; and the new demands it will make on the community of faith as it seeks to embody what it preaches. Jesus himself is portrayed as an anointed one (Christos or Messiah), i.e. a king, but the Gospel writers, especially John, present the bitter irony of attributing this title to the crucified one (John 19: 21,22).

The relationship between God and kingship has been controversial from the get-go. During the period that we call the Judges, in the Old Testament, Israel had no king, and we see both sides of the debate about whether there should actually be a king of Israel in 1 Samuel chapters 8 and 9. In chapter 8, God is opposed to the idea of an earthly king. God is their king, and they need no other. But the people do not listen and continue to clamour for a king who will “lead us out to war and fight our battles”. They want to be “like other nations” (1 Samuel 8: 19,20). In the following chapter, though, God takes the initiative in choosing King Saul, who will free Israel from the oppression of the Philistines. In other words, Saul will be an agent of God’s promise to his people to live in their land safely. This agency is further developed in 2 Samuel chapter 7, where King David is appointed, in effect, as guarantor of the Covenant between God and Israel: a Covenant that outlines a society based on justice, truth, mercy, constancy in love, and righteousness.

These two aspects of kingship continue to have an uneasy relationship. On the one hand there is what we might call the political aspiration for power, territorial expansion and competition with other nations. On the other there is the sense of Israel’s particularity, expressed in its Covenant. We see this clearly in the Psalms. There is a group of Psalms, sometimes known as the Royal Psalms, that embody the political aspirations expressed in 1 Samuel chapter 8. Psalm 2 would be a good example, in the first person, with the king himself speaking. Psalm 101 would also be among this group. Sometimes we see the king trying to fulfil the political aspirations of the people as well as the demands made by God’s Covenant. Psalm 72 (on which the hymn ‘Jesus Shall reign’ is based) shows the attempts in rather awkward juxtaposition. One is reminded of those times at the opening of the UK parliament when the monarch has to read a speech written by politicians, as if it were their own.

Alongside, and in contrast to, these Psalms which encompass the human demands of kingship are several Psalms used at the enthronement of the king. These Psalms typically emphasise God’s holiness, his precedence over the political order, and the responsibilities of the monarch towards a higher authority. Psalm 99 is a succinct example. Psalm 47 is one of my favourites.

The UK constitutional settlement separates these two alternative views of what a king is for. On the one hand we have the political arm, which exercises one kind of power. It is chosen by the people and tries to reflect their aspirations for peace, prosperity, prestige, power on the world stage and economic stability. On the other we have the monarchy which, at its best, reminds us that politicians do not have the last word. As defender of the faith the monarch maintains before us and attempts to embody what we might call the covenantal requirements of any successful society: justice, mercy, right relationship; as well as the New Covenantal demands of reconciliation and forgiveness. These are often referred to as ‘soft power’ but arguably it is the power that endures, that underlies all successful politics, and, as recent days have shown us, the power that people actually admire, respect, and wish to maintain. This is how we think of ourselves at our best. This is the people we wish truly to be.

Our lived experience is that Queen Elizabeth accepted the role that she saw as her vocation. So far as was humanly possible she worked for the monarchy to be a cohesive force in a just, merciful, diverse, loving and forgiving society. Her behaviour, prompted entirely by her Christian faith, won the admiration of the whole world. The tabloid press and some popular sentiment seriously underestimates the potential of the monarchy, expressed in our tradition over thousands of years. God’s power is a ‘soft’ power, and recognizing the strength of that power in our monarchs may perhaps help us to understand God better. Many want him to be a politician, making things happen, preventing bad things. But God is a king in the modern sense, and God has the last word.

John Holdsworth, Canon Theologian

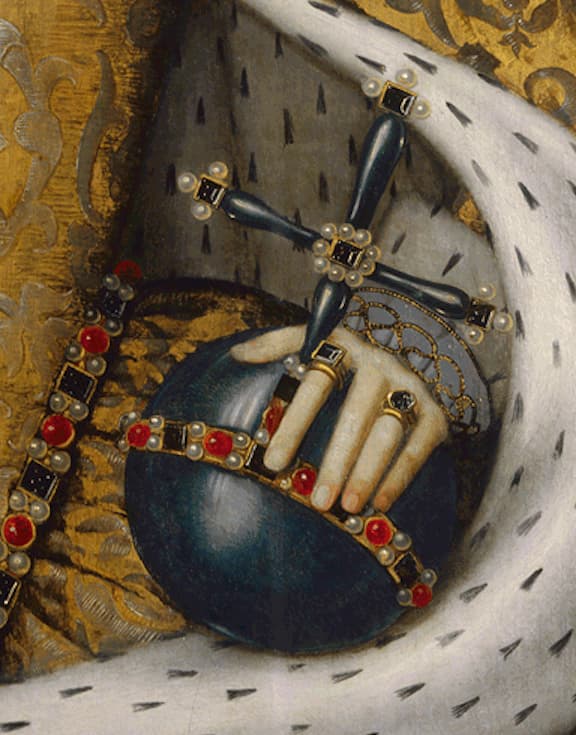

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery

Queen Elizabeth I (detail)

Unknown English artist

oil on panel, circa 1600